Responding to the Politics of ‘the Best we can Hope for’

I joined twitter a few weeks ago because it’s what a young and supple academic is supposed to do. Within a week some messaged me to say, “I see you have put on weight.” I have yet to be told that I’m looking depressed, but it’s in the post.

Aside from slights about my newly discovered corpulence, and the rampant visceral misogyny directed at women for having the temerity to venture online with opinions, the most abundant topic on my news feed concerns the forthcoming election. If the world of twitter was to be accepted as an accurate depiction of the election, one would be excused for thinking that there was some sort of genuine ideological contestation at stake; that we will see a drastically different Britain depending on what cohort of preened and screened stage politicians ultimately take office.

In turn, those who have picked their side have flooded the interweb with self-righteous ire at anyone who questions the political expediency offered by the British electoral system and contemporary party politics, or worse still those that refuse to vote and, therefore, forfeit their right to have any political opinion for the next five years. These potential non-voters are told to suck it up, to vote for the party that best represents them, even if they have absolutely no chance of winning a seat or any discernible impact on policy over the next five years. Because you never know. Every time you vote you increase the likelihood that in 50 years’ time the UK may finally adopt an electoral system that’s vaguely democratic. This argument, and this goes without saying, reifies the idea that participatory politics starts with the democratic process and radiates outwards to other, lesser, areas. That is, voting is the most important political act because governments are the defining political actors; every form of political engagement you attempt for the next five years will be defined by next month’s result.

In bolstering the importance of electoral politics a perception that something radical is at stake needs to be cultivated. You need to convince people that voting matters. That something will change. Attempts to create this perception, in turn, have descended into the binary division of politics: it’s us against them, left versus right, etc. And, of course, if you don’t support any side, you’re letting the worse side win. This binary division, however, fails to account for what is happening in contemporary British politics, and fundamentally disrespects those who have genuine doubts about the existence of any clear ideological divide between the biggest parties.

Owen Jones, a person that I like and respect for making a concerted attempt to remain engaged in the direct effects of neoliberal politics on everyday life, has, sadly, been to the fore of this drive to depict British politics in binary terms. Yesterday, he tweeted about the inherent failings of left-wing criticisms of New Labour. Above a link to a Monty Python sketch from The Life of Brian about the meaningless divisions between various Judean liberation movements, Jones stated “What is it about some people on the left who relish attacking other leftists more than the right?” The underlying argument is that we’re all on the same side, so we should be targeting the real enemies on the right: the Tories, UKIP, and DUP. The arrogance of this statement, however, resides in the clear belief that what constitutes left wing politics is clearly defined and delineated, rather than being what is precisely at stake in, not just this election, but contemporary politics in general. In demanding that we support ‘the team’, Jones is attempting to reinforce an ideal of ‘left wing’ politics that I, and many others, view as a continuation of centre-right ideology under another guise: call it New Labour or Tory Lite.

In the introduction to The Inoperative Community, Jean Luc Nancy discusses the reclamation of left wing politics from the ashes of Soviet mutilation and distortion. Nancy contends that while right wing politics has primarily concerned itself with management (managing the economy, managing immigration, managing crime, and so on), the left is, rightly, concerned with community. What Nancy means by this is that a positive left wing response to capitalist orthodoxy must start from mutual relatedness, vulnerability and dependency. In other words, a politics of the left is not simply about managing a society so that it runs efficiently as a wealth generation machine. Instead, the left is exposed to the violence, destitution and marginalisation precipitated by the individualistic self-interest that fuels contemporary capitalist societies, and responds with a concentrated political effort to assist those vulnerable and suffering, not as potential economic instruments, but as the people we need to sustain a meaningful existence. Nancy, of course, concedes that this is simply one depiction of the left, and a true left wing politics must remain in constant debate and disagreement.

What Nancy points toward is a politics of hope: a collective of people driven to challenge the systemic instruments and operations that place certain people in vulnerable and marginalised positions in order to further the interests of others. The hope derives from the belief that we can create a better political system, that we are not stuck within a particular way of understanding, and engaging in, politics. The mantel of hope has also been adopted by New Labour supporters who contrast it to the right’s purported politics of fear. The argument is that the right cultivates fear of immigrants, the poor, economic stagnation, loss of sovereignty, degradation of British identity, and so on, to convince people that left wing politics is a risk to the stability of society itself. Yet the politics of hope that New Labour responds with is merely another iteration of this politics of fear: vote Labour or you’ll get a Tory government backed by UKIP, or even the DUP. This politics of fear has even gone as far as to demarcate constituencies where you must vote Labour (because the race is close) and those where you can vote for a party that better represents your views (because it won’t affect who wins).

This politics of hope represents the most insidious form of anti-democratic sentiment presented during this election. The fact that Labour supports like Jones acknowledge that the ideological gap between Labour and the Tories is far from substantial, compounds the issue. The message is clear: Labour might not provide the genuine left wing alternative some people hoped for, but they’re a step in the right direction and a damn sight better than the Tories. Far from being a politics of hope, this is a politics of the best we can hope for. It is an acceptance that in the pursuit of political impact, those of us that want a left wing alternative to the neoliberal orthodoxy must put our ideological aspirations to the side and vote for the only viable party that has any remaining left wing vestiges. Not only does this sustain the system that maintains the two-party farce that modern British politics is built upon, it also solidifies a new understanding of what left wing politics means. An understanding that presents no political or ideological challenge to the managerialism driving contemporary neoliberal governance.

Let’s take a few examples from the Labour manifesto. In terms of economic policy, Labour promises to increase spending while cutting the deficit, reduce tax for lower earners and raise it for higher earners, reward hardworking people with higher wages and benefits, and back indigenous employers and entrepreneurs. In response to immigration, Labour will introduce new barriers to immigrants seeking benefits, strengthen borders, and usher in a number of new restrictions on people wishing to live in the UK. And as for the crisis of living standards upon which their campaign is founded, Labour will raise wages, improve working contracts and conditions, and give more support to working parents. In total, Labour’s manifesto can be boiled down to one single motif: the Tories have mismanaged Britain, and Labour will manage it in a way that benefits ‘ordinary working people’. Not only does this platform fail to provide an ideological alternative to neoliberalism, it further entrenches the ideal that people are to be valued only in so far as they are workers or potential workers (and consumers) to be harnessed by the economy. Labour do not offer a left wing politics of community, the offer a slightly different way to manage an economy that necessitates a base of workers and consumers. The vulnerable people Labour are willing to help are those who are willing to adapt to the system and work hard in their menial low paid (but slightly better paid than under the Tories) jobs. Nothing within the manifesto challenges the overarching structures that have marginalised so many Britons, and nothing within the manifesto acknowledges that there is anything inherently wrong or unjust about neoliberal economics provided they are managed properly.

The tragedy of the current election debate is that the political response to the 2008 financial crisis offers a clear platform for a left wing challenge to neoliberal managerialism. The traditional critique of the left has been that its ideals are impractical; that they simply don’t work in the real world. However, the spectacular failure of capitalist theory and ideology to function in the way it claims to (what Marx calls the inherent contradictions of capitalism) played out during the crisis underscores that the current structures of society are no less fantastical and unworkable. In stripping away the ontological hard ground upon which neoliberal ideals proclaim their essentiality, the left has the opportunity to imagine a new form of politics and society: distinct from neoliberalism, traditional socialism, and Soviet communism, an aspirational politics of change. Instead, many of those who desperately want change are so afraid of the consequences of failure that they cling desperately to a less abhorrent centre-right party portending toward left ideals.

The reasons for this fear is understandable. Life under Tory austerity has been truly horrific for many people at the margins of society. There is a clear desire to alleviate some of this pain, and Labour seem to offer the only immediate pathway to make this difference. However, the root of this suffering and marginalisation will not be addressed by a Labour government. They will, perhaps, make poverty and marginalisation more manageable for those affected, but this more palatable suffering in many ways makes it harder to challenge the structures that produce it: it makes it less dramatic, less visible and easier for us to ignore.

Labour will also make poverty and marginalisation more manageable for those of us not affected: those of us living in relative privilege and comfort. Ultimately, this is the most lastingly problematic consequence of aligning with Labour’s image of the left. In making the suffering that exists within our communities more manageable, and thereby less visible, a Labour government will allow those of us with left leanings to enjoy our lives relatively unreflectively. In juxtaposition, the stimulation for genuine political change can only come from a daily reflection upon how the privilege, comfort, and stability of our lives is built upon the hardship of others. Above all the Labour manifesto promises middle Britain that their lives will be easier and better under a Labour government. Those who buy into this message see a Labour victory as a part of an incremental set of stepping stones that will magically lead to a fair and just society without any negative consequences. The reality is that any left wing politics worth its salt must tell the truth: meaningful political change hurts. Redressing the deeply rooted imbalances and injustices in British society will costs us in privileged positions, we will have to sacrifice some of our comfort and stability if we truly want to create a fairer society. A new conception of community cannot derive from challenging those at the top (or at the bottom), it can only come if we are willing to risk our own privilege in the defence of those who have been crushed by the weight of neoliberal ideology for the last half century.

If you’re not in we can’t win!

This Saturday at 8.30 pm I am imploring everyone to watch trite national lottery quiz show, In It to Win It. The quiz is hosted by Dale Winton, a man whose banality is matched only by his propensity to resemble a newly varnished mahogany table. The questions are simple, the contestants are too, and any entertainment value is marginal at best. You must tune into In It to Win It, however, because it is going head-to-head with the return of Britain’s got Talent, and that’s worse. If you want to have any chance of stopping Simon Cowell’s smug posturing about the merits of a dancing ferret while David Walliams does his joke and Amada Holden moderately exists, then you must support Winton.

Now some people will say that you could watch the programme about China’s Wildlife on BBC4, or the classic Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure on ITV2, or even repeats of Top Gear on the iplayer while you sob profusely into an increasingly soggy poptart. But these are throw away activities, a wasted entertainment choice. They will do nothing to prevent Cowell’s cesspit of cultural faeces returning for a tenth consecutive year. If you want anything to really change you must support Winton.

Now some people will say that there are different ways to engage with entertainment. You know the types, ‘oh go read a book,’ they say, ‘or go for a walk, or attempt some form of meaningful human interaction.’ But we know that that’s all meaningless twaddle. When ordinary people think about entertainment, they think about big powerful TVs in suits, debating across the hallowed halls of primetime ratings. Some weirdos might think that you can entertain yourself with quinoa and a ball of yarn, but we need to think about saving entertainment for the masses. If you want to protect entertainment on the national level, then you must support Winton.

Now some people will say that In It to Win It is just a slightly more tolerable form of the same formula found in Britain’s Got Talent. That they’re both a form of mindless, unthinking tripe that adheres to the same mass marketed principles, and in supporting Winton you are ensuring that the meaning of mass entertainment remains fundamentally unchallenged. But do you think they’d be saying the same thing if they had to sit through another 5 seasons of Britain’s Got Talent? When the funding has been cut to the extent that it’s all sock puppets, and hosted by just Dec? Not a bloody chance! Cut the faff, this is a choice between Winton and Cowell, and if you don’t watch In It to Win It, you’ll never get rid of Cowell. If you want to get rid of Cowell, then you must support Winton.

Remember that your only chance to engage with entertainment in a meaningful way is on Saturday between 8.00 and 10.00. This is your one chance to have a real say on what you want to be entertained by. Forget the nonsense about different ways of being entertained, and hippy dippy alternatives. Being entertained means TV on Saturday nights, and if you want to be entertained in a way that benefits ordinary working people, you must support Winton.

Chris Rossdale: Militarism, Anti-Militarism and the Politics of Resistance: An Ethnography

Louiza Odysseos: Governing through impunity, Resisting through rights

On Tuesday, March 3, 4.15 – 6pm (University Place, 1.219) we are delighted to announce that Dr Louiza Odysseos from the University of Sussex will be speaking about her recent and exciting work on modes of governance and resistance through rights. The talk will be entitled Governing through impunity, Resisting through rights: Technologies of conduct within Postcolonial Governmentality. We look forward to seeing you there.

Roundtable: What is the future of Critical Global Politics?

To launch the Critical Global Politics Cluster (formerly the Post-structural and Critical Thought Cluster), a roundtable will be hosted, featuring:

Nick Vaughan-Williams (University of Warwick), author of Beyond Biopolitical Border Security: Spatial Technologies of Power in Europe (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

Marysia Zalewski (University of Aberdeen and LSE), author of Feminist International Relations: Exquisite Corpse (London: Routledge 2013).

John Hobson (University of Sheffield), author of The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760–2010 (Cambridge: CUP, 2012).

WEDNESDAY 11TH MARCH 2015, 3 – 5pm

Martin Harris John Casken Lecture Theatre

With a wine reception hosted by the Critical Global Politics Cluster from 5pm, 4th floor Arthur Lewis Building.

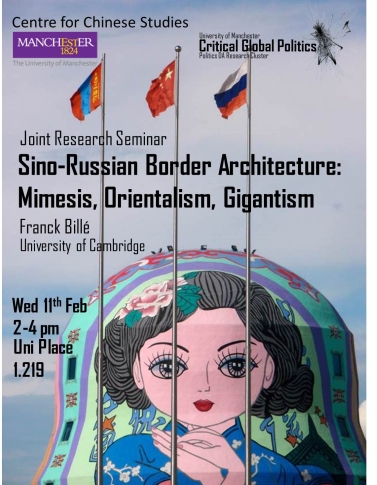

Sino-Russian Border Architecture: Mimesis, Orientalism, Gigantism

Critical Global Politics alongside The Centre for Chinese Studies are hosting a joint research seminar entitled Sino-Russian Border Architecture: Minesis, Orientalism, Gigantim with Franck Billé from the University of Cambridge.

It will be held in University Place, 1.219 at The University of Manchester on Wednesday 11th February between 2-4pm.

Annual Public Lecture: Robert Pfaller – The Unbearable Enjoyment of the Other: postmodern sensibility and the politics of anxiety

We are delighted to announce that this year’s Global Critical Politics annual public lecture will be delivered by Professor Robert Pfaller from The University of Linz, Austria. The lecture will be held in University Place 1.218 on Tuesday, January 27 between 4 – 6pm. The lecture is entitled: “The Unbearable Enjoyment of the Other: postmodern sensibility and the politics of anxiety”. We hope you will join us in what promises to be an interesting and provocative talk.

Robert Pfaller is professor of cultural theory at the University of Art and Industrial Design in Linz, Austria. Founding member of the Viennese psychoanalytic research group “stuzzicadenti”. In 2007 he was awarded “The Missing Link” price for connecting psychoanalysis with other scientific disciplines, by Psychoanalytisches Seminar Zurich – for the German edition of his book “The Pleasure Principle in Culture: Illusions Without Owners” (“Die Illusionen der anderen. Ueber das Lustprinzip in der Kultur. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2002).

His Publications include:

– 2014 The Pleasure Principle in Culture: Illusions without Owners. London/New York: Verso

– 2012 Zweite Welten und andere Lebenselixiere. Frankfurt/M.: Fischer

– 2011 Wofür es sich zu leben lohnt. Elemente materialistischer Philosophie, Frankfurt/M.: Fischer

– 2008a Das schmutzige Heilige und die reine Vernunft. Symptome der Gegenwartskultur. Frankfurt/M.: Fischer

– 2008b Die Ästhetik der Interpassivität. Hamburg: philo fine arts

– 2005 (Ed.): Stop That Comedy! On the Subtle Hegemony of the Tragic in Our Culture, Vienna: Sonderzahl (in English and German)

– 2002 Die Illusionen der anderen. Über das Lustprinzip in der Kultur, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp

– 2000 (Ed.): Interpassivität. Studien über delegiertes Genießen, Wien/ New York: Springer

– 1997 Althusser – Das Schweigen im Text. München: Fink

Workshop: The European Union: A Cybersecurity Actor?

Since its first use in the 1990s by computer scientists, cybersecurity has transcended its mere technical conception of computer security to become the expression of a worst-case scenario with devastating societal effects. The question of cybersecurity is thus no more solely examined through lawenforcement lenses; it has entered and significantly reshaped the political, doctrinal and strategic debates. How have the EU and its security agencies coped with this new and multifaceted strategic domain? A two-day workshop sponsored by the French Ministry of Defence Strategic Research Institute (IRSEM), the Manchester Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence (MJMCE), and Critical Global Politics Cluster of the University of Manchester (Political Horizons).

22nd – 23rd January 2015

Arthur Lewis Building, Board Room, 2nd floor

The programme for the workshop can be downloaded here.

For more information email: Florent Lieto (florent.lieto@manchester.ac.uk) and/or Emmanuel-Pierre Guittet (emmanuel-pierre.guittet@manchester.ac.uk).

Je ne suis pas Charlie (or why free speech is not tantamount to banter with impunity)

There is little left to be written about the attacks in France last week. On Wednesday January 7 two masked men forced themselves into the Paris offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. The men were heavily armed and proceeded to murder 12 people, injuring a further 11 as they made their escape. In the days that followed a number of other people were killed, including some of those suspected of plotting and conducting the attacks, and many more injured during the course of a manhunt to apprehend the initial murderers.

The motivation for the attacks is commonly believed to be outrage at the persistent lampooning of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons. The murders, and this should go without saying, are completely unjustifiable. Yet, the public response to the killings is also inadequate, and sadly predictable. In the aftermath millions took to the streets and social media to proclaim their support for the victims and in defence of freedom of speech. The slogan ‘Je Suis Charlie’ became a mantra for the purported reclamation of freedom of speech and expression. In this wave of indignation Charlie Hebdo has been channelled as a symbol for the right of individuals’ to speak their minds; the right to challenge opposing views and taboos, even if offence is caused.

The public fervour to jump on the ‘Je suis Charlie’ bandwagon is easily understandable: a horrific attack was waged on the Charlie Hebdo staff because the attackers took offence to what the magazine was publishing. The knee-jerk reaction is a desire to self-identify with the victims and the magazine itself. These were, after all, a bunch of people, like us, just trying to express their views in a free publication. In turn, linking Charlie Hebdo to the broader ideal of free speech simplified the narrative by presenting us with clear figures of right and wrong. It is right to endorse free speech and support those who exercise their right to speak freely. It is wrong to curtail free speech and attack those who say things we don’t agree with. This presents us with a clear black and white narrative: Charlie Hebdo are the good guys, their attackers are bad, and surely we must self-identify with the good guys? In contrast what I would like to suggest is that not only are there no good guys, but free speech, in and of itself, is an entirely grey area.

A number of pieces have already taken Western society to task for the hypocrisy of rallying under the banner of free speech, whilst, simultaneously, perpetrating a system in which who gets to speak and in what ways is rigorously censored [for example, see Cas Mudde, “No, we are NOT all Charlie (and that’s a problem),” https://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/cas-mudde/no-we-are-not-all-charlie-and-that%E2%80%99s-problem]. The underlying conception of free speech presented in these articles is that of absolute impunity: because we can’t effectively regulate speech in a fair and neutral manner, we must begin to embrace complete free speech, like Charlie Hebdo. In this respect, freedom of speech is equated to a no holds barred mode of public engagement: every slight, slur, insult or slander is permitted because everyone is entitled to have a voice, regardless of how much we may personally disagree with what is said. The logic is that by allowing everything to be said, we also have the ability to criticise and satirise everything in a Habermassian system of discursive checks and balances.

The problem with this conception of free speech is that it empties the issue of all context and, therefore, politics. If we demand absolute free speech we ostensibly wash our hands of the problem and refuse to critically engage with what this ideal actually means in practice. For, invariably, this form of unchecked discourse leads to situations in which the loudest and most prevalent voices intimidate and bully minorities and any differing views. Which, coincidentally, brings us to the case of Charlie Hebdo. The magazine and its supporters proudly boast the Charlie Hebdo mocks all religions and all viewpoints equally, it is neutral in its satire. And while the magazine has certainly lampooned Christianity, the contextual contours of ridiculing Islam and ridiculing Christianity are not equivalent in contemporary French society. Muslims in France represent an increasingly marginalised and disenfranchised minority. A hangover from France’s colonial past that is now used as a drum for right-wing politics and fears of cultural decline; banning the Hijab and questioning Muslim’s willingness to integrate within French society. It is within a context of marginalisation that Charlie Hebdo began to steadily increase the volume of cartoons openly and deliberately mocking Islam and Muslim culture: for example, hook-nosed Arabs, bullet-ridden Korans, and Muslims engaging in homosexuality and sodomy. A magazine predominantly staffed by middle-class, white males, has persistently mocked a minority group because they disagree with their theological and cultural ideals. Now, of course, this does not in any way justify the January 7 attacks. However, it does tell us something about the type of free speech that ‘Je Suis Charlie’ supporters are advocating.

The foundational myth of Charlie Hebdo and its claim to free speech is that it mocks everyone equally. This is not true, it only mocks those who are different. Charlie Hebdo is the free speech equivalent of a school yard bully, targeting anyone who doesn’t think like them or believe what they believe. It resorts to the crudest and most juvenile forms of mockery, and publishes openly racist images under the disclaimer of anti-racist satire. Charlie Hebdo is a Dapper Laughs collective making pathetic jokes and claiming banter as if it’s an adequate defence. It is a bastion of free speech in the same way a bratty child is: spewing self-righteous twaddle at anyone who has the temerity to suggest that they should just behave.

Like many others, however, I do want to live in a world that has some vestiges of free speech. Above all, the ability to state one’s opinions and beliefs without fear of violent reprisal or incarceration. And, yes, Charlie Hebdo are part of the dynamics of this ideal of free speech. But free speech, importantly, does have dynamics, it has contextual dimensions. That is why we need to be attentive when we speak: about what we say, why we say it, and to whom we address. If we want free speech, in other words, we have to be mature enough to at least try to critically reflect upon the socio-political dynamics in which we speak and write. In short, we can do better than Charlie Hebdo styled free speech. We are better than a shared economy of insults masquerading as a noble ideological mission. There are better symbols of free speech than a group of juvenile French men and women who use free speech as a tool to insult and provoke those they don’t agree with: Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, for instance, who have been hunted and, in Manning’s case, imprisoned for speaking up against what they saw as injustice, or Malala Yousafzai who took a bullet to the head for demanding education. It is for these reasons, and many more, that I am not Charlie Hebdo, and thankfully the vast majority of my friends and acquaintances are not Charlie Hebdo. Because to live in a world where our primary response to difference of culture and beliefs is to resort to crude generalised insults is frankly intolerable.

Workshop: Occupying Politics in a Time of Alterity

Occupying Politics in a Time of Alterity is the third and final workshop of the Many Voices, Many Politics series. The workshop interrogates the concept of alterity and devotes its attention to engaging with the impact of socio-political change on communities and on ideas of cultural difference as alterity; on how communities and individuals react as politically engaged creatures by protesting, rethinking, enacting and remembering otherness not just as an aberration or a triumphant moment of multiculturalism, but as part of everyday life and of identity more generally; and on the way in which alterity informs research approaches linked to ideas of becoming(s), multiplicity, acts, flows, intimacies, borders, irregularities, energies, the everyday, and aesthetics. We have contributions from across a range of disciplinary areas including international politics, law, linguistics, art, sociology, environmental studies, English literature and psychology.

The workshop is taking place on 11th/12th November 2014. For specific location details, abstracts and keynote speakers download a copy of the workshop programme.

Please email Aoileann.nimhurchu@manchester.ac.uk or Andreja.zevnik@manchester.ac.uk to register for this workshop and/or to attend the keynote talks.

Political Horizons

Political Horizons